Author: Dr. Richard Hames

Human civilization can be visualized as a global world-system, a superorganism driven by abundant energy and the interconnected activities of billions of individuals working towards shared goals. As we know there are a number of converging crises facing this world-system, and while many seek technological or market-based solutions, the root issues lie deeper within our societal production and consumption patterns. The notion of infinite growth on a finite planet is sheer folly; indeed this worldview could be the fundamental cause of the various crises we are experiencing. It’s difficult if not impossible to put a value of “enough” in a system deliberately designed for perpetual growth.

Obviously, the questions we face are complex and require deep reflection rather than quick fixes. At this critical point in the human story we’re not even sure what we’ll choose to nurture: will it be power and wealth, or life and survival? In this essay I want to point to a few related matters that might give us a clue as to what’s really needed in order to change direction. And the starting point is path dependency: which ideas or decisions from the past continue to take us in a direction that seems to be leading to collapse.

A Question of Survival or Collapse

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection has often been interpreted as justification for competition as the most critical driving force for success of the human species. This interpretation, popularized by figures like Thomas Huxley—Darwin’s staunch defender known as “Darwin’s Bulldog”—emphasised the idea of a struggle for survival, where the “fittest” individuals or species outcompeted others to secure their place in the evolutionary hierarchy. This framing found resonance within industrial capitalism, where competition in almost every public institution, from politics and education to healthcare, became a convenient societal mantra, fueling rapid technological advances but also fostering exploitation, inequality, and environmental degradation.

In contrast, Peter Kropotkin, a 19th-century Russian naturalist and anarchist, offered a counterpoint to Darwin’s narrative. His observations of the natural world, during his expeditions to cold environments like Siberia, led him to argue that survival often depended not on competition but on cooperation. Across species, he documented countless examples of mutual support—animals working together to deal with scarcity, and humans forming cooperative societies to overcome threats. Kropotkin’s work suggested that cooperation, rather than ruthless competition, was the cornerstone of survival and progress.

Fast forward to today, and it is worth asking whether humanity has tilted too far toward competition, to the detriment of cooperation, and whether this imbalance underpins many of the systemic failures we now face. From economic inequality to climate change, from geopolitical conflict to the erosion of social cohesion, one cannot help but wonder if the cult of the individual, accompanied by excessive growth, aggression, and hyper-competitiveness, have led us astray.

The comparison of Thomas Huxley’s role in broadcasting Darwin’s theory of evolution to St. Paul’s role in spreading the story of Jesus Christ is a compelling analogy. Both figures served as pivotal intermediaries, transforming the ideas and teachings of their respective founders into movements of profound historical significance. Without St. Paul’s missionary journeys and writings, Christianity might well have remained a localized sect within Judaism, and without Huxley’s public advocacy, Darwin’s groundbreaking theory would almost certainly have struggled to gain the traction it needed to reshape science and society.

St. Paul: The Cause of Christianity’s Expansion

St. Paul, originally Saul of Tarsus, played a critical role in the spread of Christianity during the first century. While Jesus of Nazareth’s teachings and life formed the foundation of the Christian faith, it was Paul’s tireless efforts that transformed Christianity into an organised global religion. Through his travels across the Roman Empire and his epistles to fledgling Christian communities, Paul articulated a theology that emphasized salvation through faith in Christ, opening the religion to non-Jews and making it accessible to a broader audience. His ability to frame Jesus’s teachings in a way that resonated with both Jewish and Greco-Roman audiences was instrumental in Christianity’s growth.

Paul was also a master of communication and organization. By establishing networks of churches and addressing their theological and practical concerns, he created a cohesive movement that could withstand persecution and internal division. His writings, which form a significant portion of the New Testament, continue to shape Christian thought and practice to this day.

Thomas Huxley: Darwin’s Bulldog

Similarly, Thomas Huxley became the champion of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. While Darwin himself was cautious and reserved, hesitant to publicly engage in debates about what were acknowledged to be controversial ideas, Huxley stepped into the role of public advocate with enthusiasm. He delivered lectures, wrote essays, and engaged in high-profile debates to defend and popularize Darwin’s work.

Huxley’s skill lay in his ability to communicate complex scientific ideas to a broader audience. He framed evolution not as an attack on religion but as a natural extension of scientific inquiry, which was appealing to the rational and empirical sensibilities of the Victorian public. His famous debates, including the 1860 confrontation with Bishop Samuel Wilberforce in Oxford, showcased his wit and rhetorical prowess, and these played a significant role in legitimizing Darwin’s ideas within the scientific community and beyond.

The Power of the Messenger

In both cases, the success of a transformative idea hinged not solely on the brilliance of its originator but also on the charisma, energy, and strategic revelation of its chief advocate. Jesus’s teachings, rooted in compassion, humility, and the promise of salvation, were revolutionary, but it was Paul who carried them beyond Judea, crafting a universal message that appealed to the spiritual and cultural needs of the Roman world.

Similarly, Darwin’s theory of natural selection was a masterstroke of scientific insight, but it was Huxley who brought it into the public consciousness, defending it against detractors and framing it as one of the cornerstones of modern science. Without his efforts, Darwin’s ideas would probably have remained within academic circles, overshadowed by scepticism and opposition from religious and scientific authorities.

The Legacy of Advocacy

The parallels between Huxley and St. Paul extend beyond their roles as advocates; highlighting the weight of timing and context. Both operated in eras of profound social and intellectual change. St. Paul’s ministry coincided with the Pax Romana, a period of relative peace and stability that allowed travel and interaction across the Roman Empire. Huxley’s advocacy occurred during the Victorian era, a time of rapid scientific and industrial progress, when the public was increasingly receptive to new ideas about the natural world.

Both figures also faced significant resistance. St. Paul endured persecution from both Jewish and Roman authorities, while Huxley encountered fierce opposition from religious leaders and conservative scientists. Yet their perseverance ensured that the ideas they championed not only survived but flourished, rewriting the cultural and intellectual landscapes of their times.

Christianity, Darwinism, and Capitalism

It is instructive to consider how two historical movements like Christianity and Darwinism can represent competing narratives about the human condition, while unfolding in ways that are linked. Christianity, as articulated by St. Paul, emphasizes divine purpose, moral responsibility, and the promise of eternal life, offering solace and meaning in a world of suffering and uncertainty. Darwinism, as championed by Huxley, presents a naturalistic account of life’s diversity, rooted in struggle, adaptation, and survival, challenging traditional notions of divine design and human exceptionalism.

Distinct narratives then, though not necessarily incompatible. Theologians and scientists alike have sought to reconcile them, arguing that evolution should be seen as a mechanism through which divine creativity unfolds. Huxley himself, while agnostic, did not view science and religion as inherently at odds, and Paul’s writings, with their emphasis on wonder and mystery, leave room for the exploration of the natural world. However, in the context of today’s economic systems, it’s possible to sense a more disturbing dynamic: a warped merger of two intimately related ideas, the unlimted extraction of natural resources and a ready supply of labour via the Calvinist work ethic, were both required in order for predatory capitalism to run.

Modern capitalism, rooted in the economic model of the Industrial Revolution, which prioritizes profit and growth above all else, is a misapplication of both Christian and Darwinian principles. From Christianity, it borrows the idea of moral superiority tied to material success. In some interpretations, particularly within the “prosperity gospel” movement, wealth is seen as a sign of divine favour, while poverty is viewed as a moral failing. This ideology distorts the Christian emphasis on humility and collective responsibility, and converts it into a justification for inequality and exploitation.

From Darwinism, capitalism borrows the idea of competition as the driving force of progress. However, this too is a distortion. Even without Kropotkin’s observations, Darwin’s insights into natural selection emphasized adaptation and the mutuality of species within ecosystems, not the ruthless elimination of the weak. In its warped form, Darwinism has been reduced to a simplistic “survival of the fittest” story, used to justify cutthroat economic practices, corporate monopolies, and the relentless pursuit of profit at the expense of workers and the environment.

Together, these distorted narratives create the ideological foundation for a system that rewards greed and punishes vulnerability. Predatory capitalism elevates competitive individualism to the status of a moral imperative, while sidelining the cooperative and communal values that are essential for community and ecological well-being. It perpetuates the myth that success is a matter of personal merit, ignoring the structural inequalities and systemic forces that shape opportunities and outcomes.

Reconciling the Narratives for a New Paradigm

I realise it might mean quite a stretch for some of us. But if the merging of Christianity and Darwinism in the form of predatory capitalism represents a distortion, then perhaps the task for humanity today is to rediscover the true essence of these narratives and reconcile them in a healthier, more balanced manner. Christianity’s emphasis on compassion, moral responsibility, and the inherent dignity of all individuals can serve as a counterbalance to the excesses of competition. Darwinism’s insights into adaptation remind us of the importance of cooperation and the interconnectedness of all life.

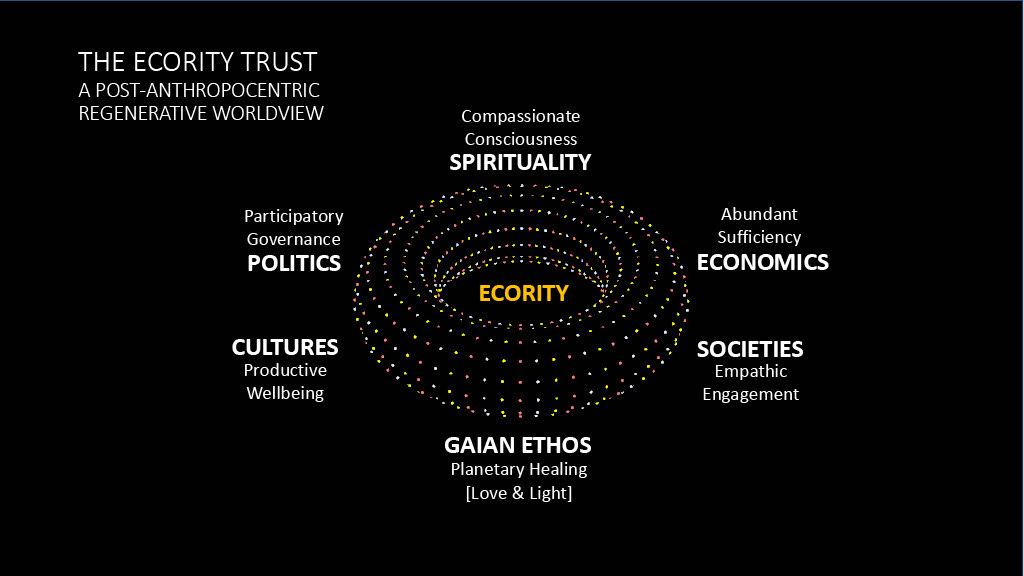

By drawing on the noblest of these traditions, we can imagine a new paradigm – a worldview that moves beyond capitalism as practised. This paradigm of ecority – a portmanteau word formed from ecology plus integrity, would prioritize collective well-being over individual gain, long-term systemic viability over endless growth, and cooperation over cutthroat competition. It would recognize that survival and progress are not about defeating others but about thriving together within the bounds of a shared planet.

Darwin and Kropotkin were not so much at odds as they were describing slightly different facets of the same truth: survival and success depend on a careful balance between competition and cooperation. Similarly, the teachings of St. Paul and the insights of Darwin are not inherently contradictory but can be reconciled in ways that promote both individual and collective well-being.

The challenge for humanity, in business and governance, is to move beyond misleading narratives that underpin predacious capitalism and rediscover the values of compassion, interdependence, and shared purpose. By doing so, we can build a world where success is measured not by how much we outcompete one another but by how well we work together to ensure a flourishing future for us all. Just as St. Paul and Thomas Huxley were advocates for transformative ideas in their time, today’s influencers and intellectuals have the opportunity—indeed the responsibility—to champion a new narrative, one that honours the diversity of life and the dignity of the human spirit.

Lessons for Today

The stories of St. Paul and Thomas Huxley remind us of the power of advocacy in shaping the course of history. Ideas, no matter how revolutionary, require champions who can communicate their significance, counter opposition, and inspire others to take up their cause. In an era of such rapid change, and faced with so many global challenges, this lesson is more relevant than ever.

As the world grapples with existential threats like climate change, new pandemics, ingrained injustice and geopolitical conflict, a world reeling from fake news and propaganda, the need for effective advocacy—whether for scientific understanding, social stability, or global cooperation—is paramount. Just as St. Paul and Thomas Huxley translated the insights of their time into movements that reshaped the world, today’s advocates must find ways to build consensus by inspiring collective action.

In the final analysis, the legacies of St. Paul and Thomas Huxley remind us that the circulation of world-changing ideas depends as much on the messenger as on the message. Both men understood the power of rhetoric, the importance of context, and the need for courage. Their stories challenge us to consider: What ideas today need champions? And who will step forward to carry them into the future?

But there’s another equally challenging theme we must explore in the context of the global problematique and that is the contrast between the Occidental worldview, and resulting world-system with all its inbuilt assumptions, and other shared belief systems, such as seen in China, Africa, and across the Global South.

Darwinism and the Occidental Worldview

It’s important to acknowledge that the emphasis on competition as the primary mechanism for what is deemed to be “success” is not universal. I appreciate this might come as a shock to those of us raised in the West, where the overwhelming saturation of Western values, the insidious strength of propaganda, and a crusading zeal akin to St Paul’s, has left us loyally supposing that the Occidental worldview is in every way superior to every other belief system, past and present.

Competition, almost uniquely, is embedded in the philosophical and cultural traditions of the Occident. Western societies, shaped by centuries of individualism, Cartesian logic, democratic principles, scientific rationalism and mercantilism, exported to other parts of the world through colonisation and a sincerely held belief in the West’s preeminence, have prioritized competition and growth as the best (only?) means of organizing a society. This worldview was reinforced by the Industrial Revolution where the “survival of the fittest” became both a justification and an instrument for domination. It forms the basis for why the US empire has been encouraged to export democracy, often at gunpoint, along with so-called “freedom” at the expense of more universal truths.

In contrast, the Sinic worldview—rooted in Confucianism, Daoism, and a long tradition of collective governance—places greater emphasis on harmony, balance, the family unit and cooperation. Confucian teachings stress the importance of relationships, community, and mutual responsibility, while Daoism advocates for living in accordance with the natural order, avoiding excessive force or conflict. These values have historically guided Eastern societies, fostering a sense of interdependence and collective well-being.

This difference in worldview becomes particularly relevant in the context of today’s shifting global order. With the rise once again of China as an economic and geopolitical powerhouse, and the relative decline of Western dominance, including the tragic erosion of moral authority which possibly began with the British Raj in India, the world is witnessing a clash—arguably not of civilizations, but of worldviews. The Western model of competition-driven capitalism, once seen as the pinnacle of progress, is increasingly challenged, just as the Chinese model of state-led development and longer-term planning gains sway. The question, then, is whether this shift will herald a rebalancing of competition and cooperation on the global stage.

The Collapse of the Old Order

The decline of Western moral authority has been evident for some time. During the height of the British Empire, colonial powers often cloaked their exploitation in the language of moral superiority and political exceptionalism, uniquely portraying themselves as sole bearers of civilization and progress. Yet the legacy of colonialism—marked by violence, continuing resource extraction, and cultural erasure—has left deep scars, and the postcolonial world has increasingly rejected Western claims to moral guidance.

In recent decades, this loss of authority has been compounded by systemic failures within the West itself. From the 2008 financial crisis to the mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, from increasing economic inequality and futile wars, to political polarization and environmental neglect, the Western model appears to many as one in decline or, at the very least, increasingly tarnished and under considerable pressure as a result. The rise of populism and nationalism in the West is a further problem, undermining its capacity for global leadership, as countries turn inward and abandon multilateralism in favour of self-interest.

In this context, China represents not just a shift in power but a potential shift in values. While China is not without its own contradictions and challenges, its emphasis on collective progress, long-term planning, and infrastructural development offers an alternative to the short-term, profit-driven focus of Western capitalism. The Belt and Road Initiative, for example, reflects a vision of interconnectedness and mutual benefit, even if its execution remains controversial.

A Return to Cooperation?

The collapse of the old order may be a good thing in the long run. The Western-dominated world-system, driven by fierce competition accompanied by relentless and unending growth, has brought humanity to the brink of ecological disaster and psychological panic. Climate breakdown, rapid biodiversity loss, wars and resource depletion are all symptoms of a paradigm that prioritizes greed and individual gain over our collective survival. The rise of a new order—one that truly values peaceful cooperation and reciprocity—could provide the paradigm shift needed to address these existential challenges.

China’s rise, coupled with the resurgence of other non-Western powers, offers an opportunity to rethink global priorities. Closely resembling the ecority model, trust in a multipolar world, where no single power dominates, may encourage greater collaboration among nations. The need to address shared challenges could serve as a catalyst for a renewed emphasis on empathic cooperation, both globally and locally.

This does not mean abandoning competition entirely. Healthy competition can drive innovation, creativity, and excellence. But it must be balanced by a recognition of human interdependence. Just as ecosystems thrive through cooperation among species, human societies must learn to work together if our species is to survive and thrive beyond the 21st century.

Striking the Balance

The question, then, is not whether competition or cooperation is better, but how to strike the right balance between the two within the new context of ecority. Competition can drive progress to some extent, but it must be tempered by cooperation to ensure that progress is sustainable and inclusive.

This balance requires a fundamental shift in values and priorities. Unconstrained growth has become a cancer on society. Economically, we need to move away from growth for growth’s sake, toward models that prioritize well-being, equity, sufficiency, ecological regeneration and peaceful coevolution. Politically, we need to embrace multilateralism and global cooperation, recognizing that not even the wealthiest or most powerful nation militarily can solve the world’s problems alone. Socially, we need to foster cultures of unity and solidarity, drawing inspiration from diverse traditions, including ancient and Indigenous wisdom traditions.

As always, education has a vital role to play. By teaching children to value collaboration and empathy, to accept shared responsibility, and practice mindful optimism, we can cultivate a generation that is better equipped to tackle the complexities of a globalized world. Similarly, businesses can adopt models of cooperative ownership and ethical governance, prioritizing long-term resilience over short-term profits.

Toward Ecority

Darwin and Kropotkin were not so much at odds as they were describing different facets of the same truth: “survival” and “success” however defined, depend on competition and cooperation. The challenge for humanity is to find the right balance—one that allows us to harness the benefits of rivalry without succumbing to its excesses and to cultivate the power of cooperation without stifling individual initiative.

In a world undergoing profound change, the collapse of the old order may be a blessing in disguise. The Western model of relentless competition and hyper-individualism, which has dominated for centuries, is increasingly seen as unsustainable in addressing the collective challenges of our time. That’s fine – not a single civilisation has endured indefinitely.

But the great challenges of our time demand a fresh approach—one that prioritizes cooperation, kinship, and interconnectedness; one that liberates the matriarchal impulse in shared responsibility for the design of systems previously wrought by men for men. By embracing a more cooperative, multipolar approach to global challenges, humanity has the opportunity to build a future that is healthily competitive but also compassionate—a future where success is measured not by dominance, but by the ability to work together for the common good.

The rise of China and the decline of Western hegemony may yet remind us of a fundamental truth: that in the great story which has become the human project, we thrive not by outcompeting one another, but by helping each other strive to be better. The recent shift in global power dynamics can serve as a catalyst for the emergence of a novel civilizational worldview, one that aligns with the principles of ecority, a paradigm rooted in ecological integrity, systems thinking, love, harmony, respect, and a deep appreciation of shared humanity—not only with one another but with the planet itself.

At its core, ecority challenges the anthropocentric and exploitative mindsets that have defined modernity, advocating instead for a worldview that values regeneration. It calls for governance systems that prioritize long-term well-being over short-term gains, economies that operate within the planet’s ecological limits, and societies that measure success by the health and happiness of their members rather than by military might or economic follies. Ecority stresses the importance of beneficial relationships between individuals, communities, nations, and the natural world—and frames loving cooperation as the foundational principle for survival and progress.

The collapse of the old order, then, is not merely an end but an opening—a chance to rethink the values and structures that have guided humanity thus far. But the West must come to its senses, accepting that China is not the enemy but an ally showing us new ways to an old destination. As the global balance of power shifts, the rise of China and other non-Western nations offers an opportunity to draw from diverse cultural traditions, including those that prioritize harmony and collective well-being. Together with the principles of ecority, these traditions can inform a new global ethic that rejects the destructive cycles of predatory capitalism and embraces a future defined by partnership, empathy, and societal well-being.

Such a vision requires courage, imagination and informed governance. It demands that we move beyond the false dichotomies of competition versus cooperation, science versus spirituality, and East versus West, recognizing instead that our survival depends on integrating the best of all perspectives. It calls for the cultivation of a planetary consciousness, where humanity sees itself not as a collection of isolated actors but as a single superorganism, embedded within and dependent upon the Earth’s ecosystems.

By adopting the principles of ecority, transcending the ingrained precepts of both East and West, we can chart a new path forward—one that honours the past while embracing the future. This is not a theoretical ideal but a practical necessity. In an era of climate crises, pandemics, corruption, nation-state fragility and geopolitical uncertainties, cooperation and interdependence are no longer an option; they are the most critical conditions for survival. The lessons of Darwin, Kropotkin, Paul, and Huxley converge here: the continuing story of humanity will not be one of dominance, but of adaptation, collaboration, and resilience suffused with love and light.

The challenge before us is immense. We can expect resistance to be unyielding for those in power have much to lose. But there’s no greater mission. By stepping into new epistemologies in order to embrace the principles of ecority, humanity can go beyond the limitations of the old order and build a future that is ecologically balanced, socially just, and spiritually meaningful—a future where we thrive not by exploiting one another or the planet, but by nurturing the relationships that sustain us all. In this great ontological reset, we may finally rediscover the truth that has always been at the heart of survival: we are stronger together.

Source: The Hames Report